A blog post by Dr Melanie Bassett, Liverpool John Moores University, reflecting on the recent workshop organised by Gateways to the First World War and The National Archives.

“I didn't know anything about black seafarers never mind them ever being in the First World War.”

Audience feedback, 2019.

Following the great success of a workshop hosted at the University of Portsmouth in January 2018, Gateways to the First World War and The National Archives delivered on their promise to hold an event aimed to inspire community groups to explore an often overlooked aspect of World War One history. BAME Seafarers in the First World War. Projects, Resources and Support was held on 24 January 2019 in the National Archives’ impressive new public events auditorium at Kew.[1] It mixed presentations offering practical help with project funding, and speakers who had conducted their own research. The National Archives also ran their popular What’s On event during the day, which showcased the research being undertaken by high-profile academics and public historians. During the break the National Archives and Asif Shakoor also showcased their collections of artefacts relating to the day’s theme. The well-attended event highlighted the public appetite to learn more about BAME histories in Britain, and has hopefully opened up new possibilities for uncovering the hidden history of BAME seafarers in the future.

Prof Brad Beaven introducing Gateways to the First World War

Prof Brad Beaven introducing Gateways to the First World War

Professor Brad Beaven from the University of Portsmouth, a Co-Investigator of Gateways to the First World War, opened the event by explaining the purpose of Gateways and the projects it has been able to support thanks to grants from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the HLF. These have included providing funding for open day events, study days, exhibitions, a seminar series, conferences and public talks, dramatic performances, and even musical concerts. Brad also leads the University of Portsmouth’s Port Towns and Urban Cultures research group, which specialises in fusing maritime, social, and urban history in order to better-understand the unique nature of coastal communities. He displayed research on the Royal Navy’s Battle of Jutland Casualties; undertaken with a research award from Gateways; and proposed a bold mapping project which would chart BAME seafarers in the Merchant Navy.[2]

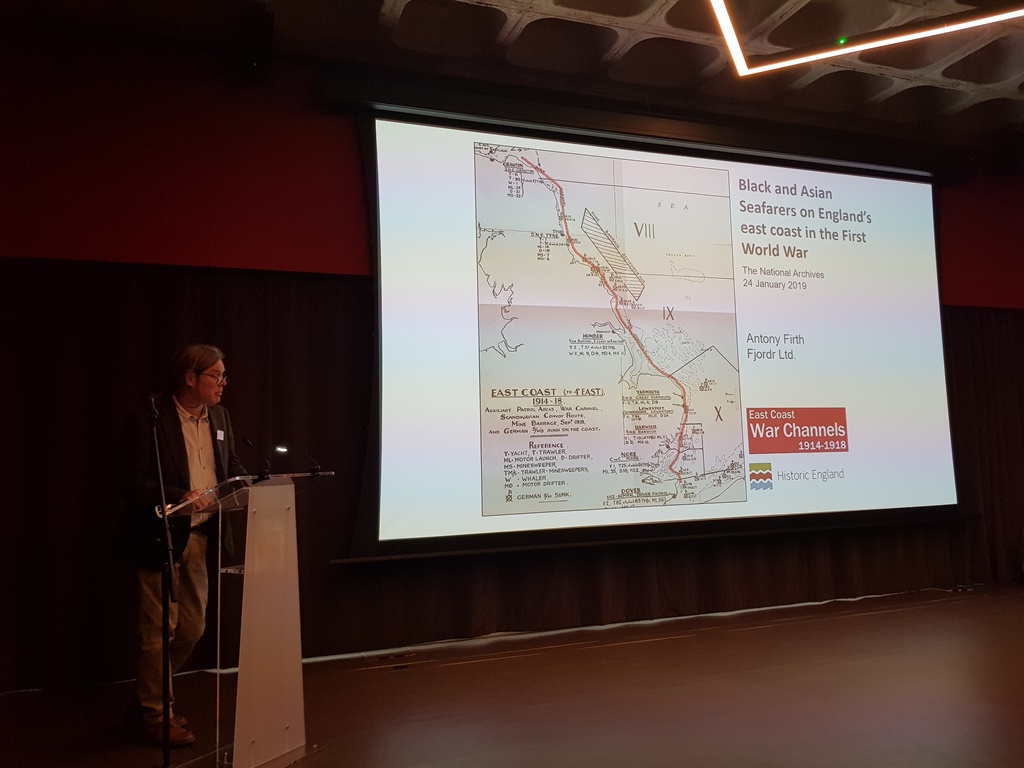

Next, Marine Archaeologist Antony Firth (Fjordr) highlighted his research into East Coast War Channels, funded by Historic England. This research led Antony to dig deeper into the backgrounds of the crews of the shipwrecks he was researching. He noted that although there were many BAME seamen serving aboard British merchant ships, they were not commemorated in the same way that white seamen were. For example he showed the deaths of crew from the SS Audax, which was torpedoed off the North Yorkshire coast in September 1918. Whereas Gustav Johansson, a Swedish Engineer, was commemorated on London’s Tower Hill Memorial for ‘men of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets who have no grave but the sea’[3]; Ghaus Muhammad and Muhammad Abdul, a ‘Donkeyman’ and a ‘Fireman’ aboard the ship, were memorialised in Mumbai.[4] Antony highlighted that there was a disconnection between the last resting place of these sailors and the contribution they had made to the war effort. Antony argued that men such as Ghaus Muhammad and Muhammad Abdul were invisible to the British public, which has caused problems in the perception of the effort of BAME seafarers during the First World War.

Antony Firth, Black and Asian Seafarers on England’s East Coast in the First World War

Antony Firth, Black and Asian Seafarers on England’s East Coast in the First World War

Antony drew attention to the fact that there are records out there which will help to quantify and reveal the BAME seafarer war effort. In particular, he cited such resources as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records; Foreign Office Records and the Registry of Shipping and Seamen Index of First World War Mercantile Marine Medals and the British War Medal both held at the National Archives; and the National Maritime Museum’s 1915 British Merchant Navy Crew Lists, which would be useful places to start researching the stories of these men further.

However, Firth’s presentation also addressed the question of why BAME seafarers are not better represented in the history of the First World War. He quoted John Siblon’s assertion that Imperial War Graves Committee policy

... not only represented a spatial segregation of Black seamen from their perceived white superiors, despite serving and dying on the same ships, but also a reflection of the premise that only White Europeans could be culturally commemorated in the memorial landscape of the metropole.[5]

Thus, Firth’s presentation served as a ‘call to arms’ for those interested in the maritime history of the First World War. He noted that the absence of seafarers of any background has largely been overlooked due to a dominant Western Front First World War narrative. However, he argued, this has been further obscured for the members of the mercantile marine community, particularly people of colour. Antony was confident that this omission could be reversed and he highlighted the advantages to uncovering a BAME history of First World War seafarers. Antony argued that by doing further research on this topic we would not only know more about the war graves of men situated just off our shores, but it would also serve to underline the diversity of context and experiences of those who fought during the First World War.

‘The Muscles of Empire’, Rozina Vishram and Florian Stadler explain lascar histories of the First World War

‘The Muscles of Empire’, Rozina Vishram and Florian Stadler explain lascar histories of the First World War

The National Archives hosted their What’s On event from 12-2pm, which was complimentary to the Gateways programme. It included three presentations by researchers prominent in the field of BAME history. Rozina Visram (author, Asians in Britain) and Dr Florian Stadler (University of Exeter) presented their research on Indian ‘lascar’ sailors: Dubbed the ‘muscles of Empire.’[6] Visram and Stadler’s research highlighted the rich archives available to those wanting to study this group of seafarers. As Visram pointed out, the term ‘lascar’ was used by European colonialists to describe people of very disparate backgrounds from South East Asians to Arabs. Its translation from Urdu meant ‘army’, which underscored an important factor in the importance of the historical understanding of ‘race’ and the invention of ethnic groupings. Visram and Stadler catalogued the constructed hierarchies of the seafaring system, which resulted in the types of jobs and wages lascar sailors were to expect. They were paid considerably lower than white seafarers, and were employed in the worst, most dangerous working conditions such as in the engine rooms as ‘Firemen’ and ‘Donkeymen.’ A most interesting aspect of their research was into the little-known incarceration of lascar sailors in German internment camps during the First World War. According to Stadler, lascar sailors were the largest group of imprisoned seamen in Germany. However, still very little is known about them. Both Stadler and Visram highlighted the need for more research to be done on the experiences of lascar prisoners of war. This was due in part to incomplete or inaccurate record keeping – one common problem in both English- and German-language records is the misspelling of names and omission of address-keeping, making the job of tracing lascar POWs especially tricky. Again, this highlighted the inherent lack of consideration for the wellbeing of non-Westerners in post-WW1 society.

Prof Santanu Das shows a picture of interned lascars in Germany

Prof Santanu Das shows a picture of interned lascars in Germany

Next to present was Professor Santanu Das (All Souls College, Oxford), whose research complimented many of the strands running through the day so far. He added nuance to the way that the public memory of lascars had been rationalised after the First World War by drawing attention to the Bombay 1914-18 war memorial in Mumbai, and the Lascar Memorial in Kolkata, who bore the ‘double cross of race and rank.’ Das underlined again how ethnically diverse the lascar workforce was by quoting the author Amitav Ghosh:

He had thought that the Lascars were a tribe or nation, like the Cherokee or Sioux: he discovered now that they came from places that were far apart, and had nothing in common, except the Indian Ocean; among them were Chinese and East Africans, Arabs and Malays, Bengalis and Goans, Tamils and Arakanese.[7]

Das’s research had led him to the Humboldt Sound Archive, Germany, which holds recordings of non-White prisoners interned in Germany. Das shared the oral testimony of a Bengali lascar, which could be used to examine their treatment in camp, and their day-to-day experiences. However, he questioned the recording as a source, and assessed that the recordings may have acted as propaganda.

Writer and historian Steven I Martin presented his findings on the contribution of sailors from Africa, the Caribbean, and Britain’s Black Communities. Martin related that he was keen to delve into the motivations of members of Britain’s Black communities to find out what motivated them to get involved in the war effort. His talk particularly focused on the relationship between the port town environment and seafarers of African and Caribbean origin. Martin showed examples of sailors’ hostels such as the Strangers’ Home for Africans, Asiatics and South Sea Islanders in London, and the proliferation of other boarding facilities in major port cities such as Liverpool through shipping companies such as Elder Dempster. Through his research Martin was able to show direct correlations to pre-First World War ethnic communities and maritime industries; attesting that 15% of men in these settled communities chose to join the Royal Navy.

After a generous lunch Anne Dodwell from the HLF gave a talk about Heritage Lottery Funding and tips for successful bids. She also highlighted some examples of projects recently funded by the HLF under the First World War: Then and Now grant scheme, which can be found below. The current grant scheme was coming to an end and Anne was unable to reveal plans for the HLF’s new strategic framework to be able to point the audience to new streams of funding. However, they are now available online. We would urge anyone who was inspired by the event, or is interested in uncovering BAME seafaring histories of the First World War to get in contact with Gateways, and we would be delighted to consult on your grant application.

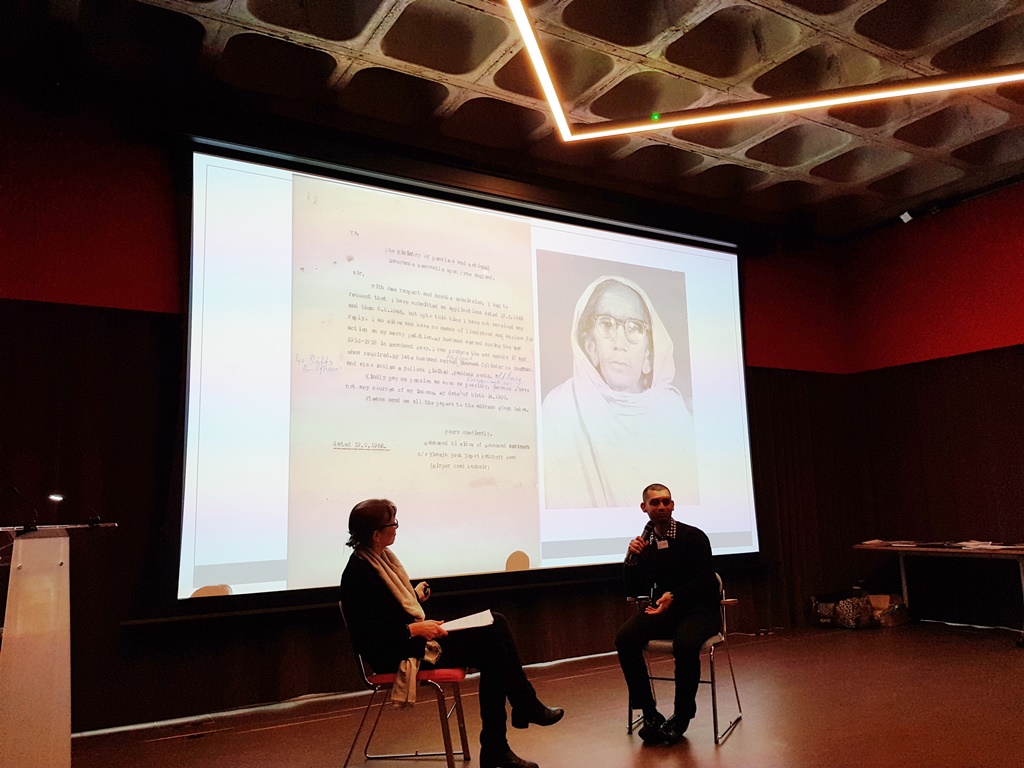

A Question and Answer session between Asif Shakoor and Dr Georgie Wemyss (University of East London) followed which unravelled the heart-warming story of Asif’s search for his grandfather’s First World War Medals. Asif’s example gave heart to anyone who is unfamiliar with their own BAME seafaring history having found out about his grandfather’s service by chance when sorting through his grandmother’s house in Pakistan. He attested that before he started he did not even know what the Mercantile Marine Service was! Although much of the story can be read on the Port Towns and Urban Cultures website, there were a few more updates, and twists and turns in the research which encompassed the great usefulness of social media for reaching out to people across the world who are willing to help you. In this case, Asif was aided by a follower of his story in Canada who was able to visit the shop of a man reported to have bought one of his grandfathers’ medals.

Asif Shakoor and Dr Georgie Wemyss in front of a picture of his grandmother. Asif explained that ‘Women are the keepers of history.’

Asif Shakoor and Dr Georgie Wemyss in front of a picture of his grandmother. Asif explained that ‘Women are the keepers of history.’

A great example of a community-based BAME seafaring project was shown by Gaynor Legall’s presentation on Tiger Bay and the World.[8] While it has been recorded that some 1400 ‘coloured seamen’ from Cardiff lost their lives during the First World War, the efforts of Gaynor and her group have been able to showcase Cardiff’s rich seafaring and cultural heritage beyond mere statistics. During the talk she outlined the demography of Cardiff’s BAME population, which stood at around 700 persons by the outbreak of war, and 3,000 at its conclusion. Migrants from Cape Verde, Somalia and Yemen were shown to have a long history of settlement in the Welsh capital. Similarly, Census records highlighted the presence of Caribbean migrants and where they had settled in Cardiff’s Bute Town, or Tiger Bay, area. Gaynor also explained the structures of inequality imposed on the BAME seafaring community whereby men were paid differently based on assumptions about race and their innate seamanship.

Tiger Bay was particularly touched by issues of racial tension. Gaynor cited the anti-Irish riots of 1848, and the seamen's strike and anti-Chinese ‘Laundry Riot’ in 1911 as precursors to anti-foreigner ‘race riots’ in 1919. This increasing governmental control could be witnessed through the passing of the Aliens Order (1920), and the Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order (1925). As a consequence of racial tensions following the war Cardiff authorities also set up a ‘Repatriation Committee’ to convince non-White seamen to leave the country.

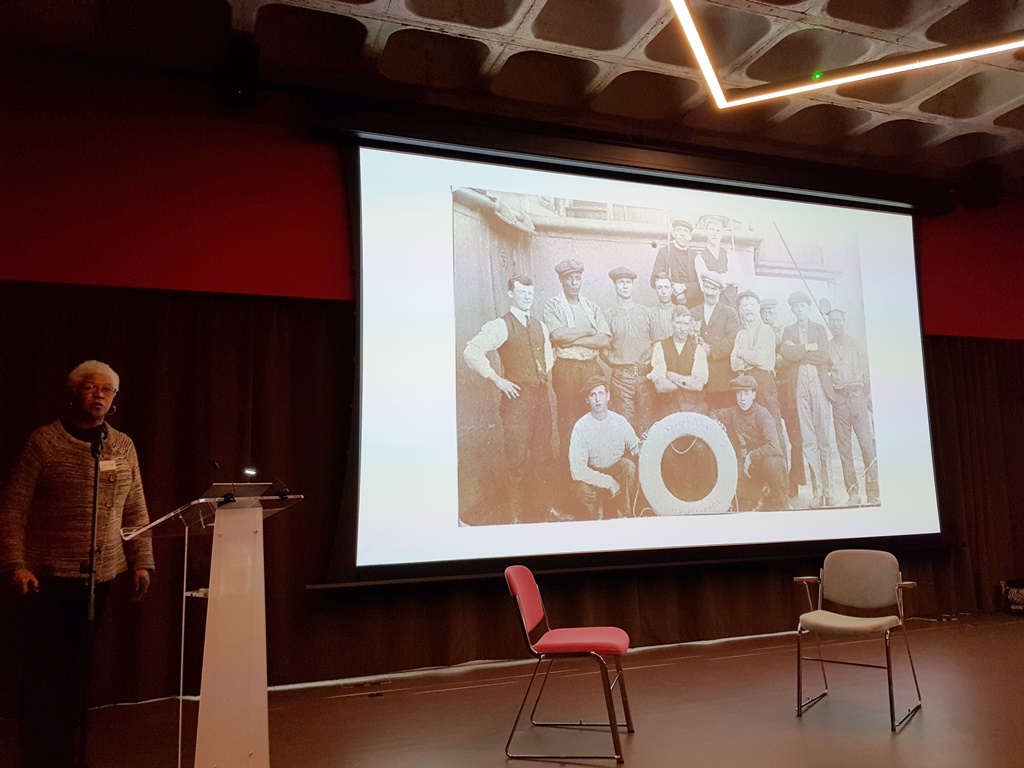

Gaynor Legall next to a photograph featuring her father and great uncle

Gaynor Legall next to a photograph featuring her father and great uncle

The most compelling part of the talk was Gaynor’s own personal story. Her grandfather James had been born in Jamaica, British West Indies, and had been awarded for his service during the First World War, also earning a Long Service Medal. At one point she showed her grandfather and great uncle next to each other in a group photograph aboard a ship they were crewing. The striking point being that her great uncle was from her maternal side, and was of White Welsh origin, while her grandfather was Afro-Caribbean. These men, who had served together, represented the mixed heritage of the speaker and signalled the diverse heritage of many British citizens. Indeed, Gaynor attested that before undertaking research on Tiger Bay she had no idea that it would have anything to do with her own life. However, she found that her own history was more personally intertwined than she had previously thought. Through stories like Gaynor’s and Asif’s we can see that there are certainly many, many more examples of First World War seafaring heritage within the BAME community which could be uncovered. As one audience member tweeted: ‘Gaynor’s words of wisdom: Don’t leave it too late! Ask your family about names and dates for any family records!”[9]

The last speaker of the day was John O’Brien who showcased the vast collection at the British Library and its potential for research into the histories of BAME seafarers. He particularly focused on the India Office Records (IOR), and also highlighted the online resources in their World War One and Asians in Britain databases. John has also blogged about potential research topics arising from the IOR in the piece Indian Seamen and the Steamship ‘Rauenfels’ during World War One. O’Brien has offered his help to those interested in the India Office Records and invited them to contact him via ior@bl.uk

Conclusions

Until recently the public’s general perception of the First World War has largely overlooked the seafaring aspect of the war effort as it struggled to come to terms with the extreme carnage which was experienced in the trenches of the Western Front. The BAME Seafarers in the First World War event highlighted the interwoven histories of the British Empire and the sea. The presentations and subsequent discussions brought up many similar themes involving contemporary attitudes towards ‘race’ and the assumptions based upon it. Historical rationalisation of the War in its immediate aftermath effectively ‘whitewashed’ it in order to fit in with the narrative of a war fought by European super powers. The makers of Empire and leaders of Britain were blinkered in their understanding of the multitude of races and cultures within Britain and throughout the Empire who also sacrificed themselves for the war effort. As a consequence, this fundamentally undervalued the war work of a significant section of the British Imperial population. What the day ultimately showed is how much rich primary source evidence is available to redress this narrative. I am looking forward to see the new histories that may be uncovered!

We would like to thank all the attendees, the speakers, and The National Archives, who all added so much to the event.

Selected feedback for the day

We thank everyone for their feedback on the day. We were pleased to hear from so many, including community historians, teachers and PhD candidates. Please read below some of the comments on the day:

Q: What have you enjoyed?

“Learning new research funding, people and their experiences.”

“The range, pieces fit in well together.”

“Everything”

“The diversity of speakers! Usually there is a dearth of speakers / researchers of a BAME background anywhere.”

“All of it - good variety. Also appreciated the documents exhibition.”

“I learnt new information about the role of BAME seafarers and role in WW1.”

“Meeting new people, hearing their stories.”

“Black and Asian seafarers from England's East Coast. Accounts of black and Asian seafarers in the First World War. The interview of Asif Shakoor; Tiger Bay.”

“Learning about different nationalities, their experiences and conditions.”

“Very much - useful and full of ideas.”

Q: Did you feel you gained new knowledge?

“Yes! Found new repositories, archives, projects, missing research links.”

“ Yes. For e.g., settlement of black community in ports is related to their role as seafarers.”

“Yes because I didn't know anything about black seafarers never mind them ever being in the First World War.”

“Found out more about BAME esp. those in the merchant fleet.”

“Mapping the origin of sailors at Jutland. How to conduct surveys of HLF projects.”

“Yes enjoyed the interview with Asif Shakoor.”

“Yes re POW camps and the conditions in them.”

“Yes - the different historians, groups and their work.”

Links and useful resources

There are a number of great resources to consult on the theme of BAME histories and seafaring histories. I have collated a list on the Port Towns and Urban Cultures website, a few which were specifically mentioned during the event were:

British Library:

HLF-funded projects:

- The Empire Needs Men, a project by Narrative Eye to help London community groups research the African and Caribbean contributions to the First World War, and was then reinterpreted for a younger audience in the form of a musical by Batanai Marimba.

- From the Great War to Race Riots, which enabled members of Liverpool’s Black communities to explore their First World War family history and the stories of black servicemen.

- Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War, was a project which was also part-funded by the Maritime Archaeology Trust which researched and recorded First World War shipwrecks around the coasts of Britain. Anne pointed out that the project had created an accessible database and a host of educational resources, that could be used in new projects. In particular to the event’s theme, she drew attention to their online booklet covering Black and Asian Seamen related to some of the wrecks.

National Maritime Museum, Crew Lists of the British Merchant Navy – 1915 https://1915crewlists.rmg.co.uk/

SOAS, Ruhleben 1914-1918: African Diaspora and Arab Civilians Interned in Germany, curated by Sonia Grant (ran until end of March 2019) https://www.soas.ac.uk/gallery/ruhleben-1914-1918/

- Review by Jo Stanley in Morning Star https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/c/out-margins-history

University of Warwick, The Seaman, 1914-1918: Index of names https://warwick.ac.uk/services/library/mrc/explorefurther/subject_guides/family_history/seamen/ww1names/

Notes

[1] Sonia Grant was unable to present due to unforeseen circumstances. The schedule was amended and Anne Dodwell’s presentation was rescheduled for after lunch. To view some of Sonia’s research you can visit her current exhibition at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London, Ruhleben 1914-1918: African Diaspora and Arab Civilians Interned in Germany, which runs until end of March https://www.soas.ac.uk/gallery/ruhleben-1914-1918/ Dr Jo Stanley has reviewed it in the Morning Star https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/c/out-margins-history

[2] For those interested in developing a project in partnership with Professor Beaven, please contact him via the Gateways to the First World War website https://www.gatewaysfww.org.uk/content/contact-us

[3] Statement from Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) ‘Tower Hill Memorial,’ https://www.cwgc.org/find/find-cemeteries-and-memorials/90002/tower-hill-memorial last accessed 08/02/2019

[4] Fireman – Like a ‘Stoker’ on Royal Navy ships. A Fireman would keep the engines fed with fuel in order to produce the steam power to sail the vessel. Donkeyman – Would be in charge of keeping the Donkey Engine (a small steam engine used for task aboard ship) running. They would oil and grease all moving engine parts, and also stoke the engines.

[5] John Siblon ‘Negotiating Hierarchy and Memory: African and Caribbean Troops from former British colonies in London’s Imperial Spaces’. The London Journal, 2016, 1-14.

[6] A nod to F J A Broeze, ‘The Muscles of Empire – Indian Seamen and the Raj 1919-1939,’ Indian Economic and Social History Review (1981) XVII, no.1: 43-67.

[7] Amitav Ghosh, Sea of Poppies, 2008, p.12.

[8] It was created in partnership with the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales/Comisiwn Brenhinol Henebion Cymru, and stemmed from the U-Boat Project/Prosiect Llongau-U 1914-1918.

[9] @bydbach, Twitter, 24/01/2019, https://twitter.com/bydbach/status/1088467870839914501, last accessed 18/02/2019.